THE BRONZE AGE

The following pages are added here from the warlord games website. Recently there was a series of excellent articles posted by noted Bronze Age historian Nigel Stillman, which are being added to on a regular basis. Much of what Nigel has posted is accepted wisdom but interpretations of some aspects of the period may never be known or can be interpreted in other ways. Regardless, his discussion gives a very nice war gamers focus on the period and thus is of immense value to the Bronze Age gamer and amateur historian. Nigel wrote the WRG book on the Armies of the Near East and it is a title most definitely worth picking up (see the Reading section for details)...his contributions are to the benefit of us all.

The Warlord site has numerous other related articles on the Bronze age and is a useful place to keep abreast of the Bronze Age releases by Warlord Games, who picked up the superb 28mm Cutting Edge Miniatures range and continue to expand on it.

It's all placed here so it doesn't get lost in the internet ether with the passage of time as these things often do!...nice one Warlord.

PART I

Sumerians and Akkadians

HISTORY: SUMERIAN & AKKADIAN WARFARE PART 1 – MILITARY DEVELOPMENT

A renowned Ancients wargaming expert, archeologist and author, Nigel Stillman is a well respected name in our hobby and we’re delighted to have Nigel writing for us. Here Nigel provides a detailed account of Early Bronze age warfare. Part 1 covers the available sources of information for this long distant era and examines the distinct phases of military development that set apart the armies of the period.

HOW WERE BATTLES FOUGHT IN ANCIENT SUMER AND AKKAD?

Within a few generations of the rise of the first cities on the plains of Mesopotamia, in the ancient lands of Sumer and Akkad, the oldest organised armies went into battle. From surviving records and artworks, continuously being revealed by archaeological investigation, we can attempt to reconstruct how these armies were organised and how they fought.

Naram-Sin, the strong, King of Akkad

When the four corners of the world made war on him

He was victorious in nine battles in a single year

…And he captured those kings who had risen against him.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION

There are three sources of information for reconstructing how battles were fought in ancient Sumerian and Akkadian times and how the armies were organised and equipped. These are:

Artefacts

- Finds of weaponry and equipment from archaeological excavations in the Middle East, and especially in Mesopotamia. The name itself means ‘the land between the rivers’, these being the Tigris and Euphrates, of course. Most of this region now lies within the modern countries of Syria and Iraq. Agriculture and civilisation developed here several thousand years BC, leading to the rise of numerous cities. Over time, layer upon layer of occupation debris accumulated beneath each city, creating a huge mound, known as a ‘tell’, on top of which stood the latest city. Many such tells are now archaeological sites. Excavation frequently reveals artefacts including weapons of war.

For example, in the royal tombs of Ur excavated in the 1920’s, as well as tombs at the site of the ancient city of Kish, remains of four-wheeled battle-carts were uncovered. The actual armaments can be compared to pictorial representations on monuments, which often depict them in what is to us a distorted perspective, helping to clarify such things as the design of a battle-cart. Pottery and bronze models of battle-carts are particularly useful. One wonders whether they were intended for a ritual game of soldiers! Incidentally, a board game was found in the royal tombs of Ur.

Art

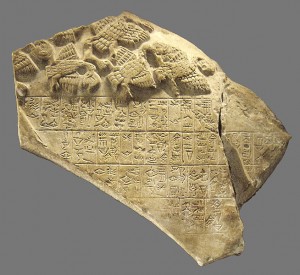

- Carvings, inscriptions and depictions of warfare on monuments have also been discovered in excavations. Notable examples include the ‘Stela of the Vultures’ from Lagash and the ‘Standard of Ur’ from the royal tombs. This type of evidence tells us what the troops actually looked like. A victory stela was an inscribed slab of stone erected to record and commemorate a victorious military campaign. It would be set up in the temple precincts in gratitude to the patron god of the city, and as a reminder to future generations to uphold the rights of the city against foes and rivals. Statues of rulers with inscriptions recording their campaigns served a similar purpose. Many such monuments survive as fragments, having sometimes been smashed by enemies when they managed to overthrow the city. Others were carried off to far away places, such as Susa in Elam, as booty by later conquerors.

Texts

- Written records in the form of clay tablets inscribed in the cuneiform script. Excavations have unearthed archives of thousands of these tablets. Many still await translation. These included the bureaucratic and diplomatic records of the city-state, ritual texts, literature and historical records such as king lists. The scribes of ancient Mesopotamia and surrounding regions used clay as a writing material, unlike the Egyptians of the same period who wrote on papyrus. The soft clay was impressed with a wedge-shaped stylus and baked to create a permanent record, which can survive for millennia. The first languages to be written in this way were Sumerian, Akkadian and Old Elamite, as well as the dialect of Ebla.

These scripts reflect the languages spoken at this time in Mesopotamia and surrounding lands. Apart from recording the details of battles and campaigns, such documents provide first-hand contemporary evidence for how armies were organised and equipped, as well as preserving the messages sent by rulers to each other and to their generals concerning the reasons behind and conduct of their wars. A huge amount of information can be discovered in these texts. Texts supplement inscriptions, as for example in the case of the long border war between the city of Lagash and her great rival Umma, which now can be reconstructed from many sources, each revealing new details and anecdotes. Since texts already found are still being translated and studied, we can expect continuous new information from cuneiform scholars about the military history of Sumer and Akkad.

THE EVOLUTION OF ARMIES

The evidence spans a period of at least a thousand years, from as far back as 3000 BC to the end of the Sumerian era around 2000 BC. Within this timespan we can distinguish four main phases of military development:

The Uruk period before circa 3000 BC.

- The Uruk period before circa 3000 BC. During this time Uruk was the pre-eminent city and Sumerian civilisation spread outwards over a wide area of the ancient Middle East resulting in the widespread rise of cities. The core region was Sumer, which is Southern Mesopotamia. Writing was a fairly new idea and records are sparse and mainly comprise economic texts. The earliest cities were ruled by priest-governors on behalf of the patron god. The rapid expansion of agriculture and consequent rise in population resulted in a crisis towards the end of this phase, leading to the beginnings of warfare between rival cities. The proper organisation of farming land and access to marginal ‘steppe’ land and water were vital to survival in this region. Irrigation canals were dug across Sumer demarcating the territories of different cities. A crucial region was the land of Akkad, located to the north of Sumer where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers flowed close together. Control of this area led to Kish becoming the leading city for a time.

The Early Dynastic period from circa 3000 BC to circa 2300 BC.

- The Early Dynastic period from circa 3000 BC to circa 2300 BC. This is the phase when armies are organised in every city, and military development is rapid due to frequent conflict between them. As the name suggests, we know of several dynasties that existed during this time. Most notable were rulers of Ur, Uruk, Lagash, Umma, Kish, Sharrupak, Nippur and further afield; Susa, Mari, Ebla and Hamazi. At this time, city-states were frequently engaged in hostilities over territory. Every so often a city would gain a temporary ascendancy, referred to as ‘kingship’. The new title of Lugal, usually translated as ‘king’ but literally meaning ‘Great Man’, was originally applied to a war leader who vanquished another city. Sometimes, several cities acted together in temporary alliance. A city was now ruled by a Lugal because it needed a commander for its army.

It was no longer enough just to call up the tenants of temple lands and send them out with slings. A city needed a proper standing army, or at least a war leader with his household troops, always ready, and which could be augmented by militia. The records of this time are full of variations of Sumerian terms for ‘soldier’ as if the scribes were trying to get a grip on this new profession. Alongside this organisational development came technological innovation and new methods of fighting. The most striking of these was the close formation of infantry and the rapid, if rickety battle-cart drawn by wild asses. Chariots appeared early in this period, as shown by depictions on pottery. One of the best-documented and most studied wars of this period is the border conflict between the cities of Lagash and Umma, which lasted on and off for 100 years.

The Akkadian Empire from circa 2300 BC to 2100 BC.

- The Akkadian Empire from circa 2300 BC to 2100 BC. This was the empire created by the conquests of Sargon, the king of Akkad. The land of Akkad and the Akkadian language are actually named after the city. This was a time of big armies that combined troops from many city-states and out-lying kingdoms. Towards the end of the preceeding phase, successful commanders, such as Lugalzagesi of Uruk, had managed to subjugate several rival cities to create a temporary empire. It was Sargon, an inspired commander of obscure origins, who seized power in the city of Kish and went on to vanquish Lugalzagesi and conquer all of Sumer. He founded the city of Akkad (or Agade) after which the land of Akkad is named. In further campaigns he established a widespread empire, extending well beyond Sumer and Akkad. His successors in the Dynasty of Akkad held on to these conquests and expanded the empire despite rebellions.

At its furthest extent, the Akkadian Empire stretched from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea and beyond into Anatolia. A new name had to be found to describe an imperial king and this was ‘Ruler of the Four Quarters’. Efforts were begun to introduce new methods of governing such a wide realm in order to counteract the tendency of cities and tribes to reassert independence at every opportunity. Akkad became a powerful capital, but in due course the empire began to crumble. The Sumerian cities were determined to win their independence. Akkadian governors were ousted in favour of rebel rulers, leading to the need for frequent re-conquest by Akkadian kings. Ultimately it was climate change in the form of increasing aridity in upper Mesopotamia, combined with the incursions of barbarous Gutian tribes from the Zagros Mountains in Iran, which brought down the empire. One notable military development during this phase was the increasing use of the powerful composite bow.

The Third Dynasty of Ur from circa 2100 BC to circa 2000 BC.

- The Third Dynasty of Ur from circa 2100 BC to circa 2000 BC. In the chaotic aftermath of the fall of Akkad, the Sumerian cities – especially Uruk and Ur – fought back against the Gutians and ousted their chief from power. Initially, Utu-Hegal of Uruk defeated the Gutian king Tirigan in a well-reported campaign in which the Gutian king fought from a chariot. Utu-Hegal’s ally was Ur-Nammu of Ur. After gaining the kingship of Sumer and Akkad, Ur-Nammu established the Third Dynasty of Ur (Ur III). Ur-Nammu and his successor Shulgi created a new ‘Sumerian’ Empire that was almost as extensive as the former Akkadian Empire. A huge effort was made to organise and standardise throughout the land, probably in reaction to the same factors that had caused the Akkadian Empire to crumble.

The maintenance of road networks, transport and supply were emphasised. The new empire has sometimes been compared to a ‘communist regime’ because most subjects were employed by the state and owed state service. A huge number of bureaucratic texts survive from this time, some of which document military organisation and campaigns. The different elements of Sumerian and Akkadian armies continued to evolve. An important development included the increased use of tribal and foreign auxiliaries including Amorites, Gutians and Elamites. Another development was the appearance of the horse, known as the ‘foreign ass’, although they were rare and their use limited to a few despatch riders or as another potential draught animal for battle-carts.

The kings of Ur built a long wall dividing upper Mesopotamia from Sumer and Akkad called Muriq-Tidnum. This was supposed to keep out Amorite nomads (known as Martu and Tidnum). Elam was put under a governor or viceroy. These measures did not save the empire. A general reported that the Amorites had outflanked the wall by going through the highlands to invade Lower Mesopotamia, disrupting agriculture and causing famine. At this point the king of Simashki, a land to the north of Elam, seized power in Elam, asserted independence, invaded Sumer and finally sacked Ur itself.

TECHNICAL NOTE

In this brief outline I refer to the conventional dating as used in most books. The chronology of the whole period is as yet uncertain, with several hypothetical chronologies being investigated and debated by scholars. I favour the shorter chronological schemes, which if correct could reduce the dates given here by at least 100 years. This era in Mesopotamia is contemporary with the Old Kingdom, the ‘pyramid age’ of Egypt, and in any revised scheme the dating of both would change in tandem. Severe drought probably played a part in the fall of the Akkadian Empire, which suggests that this happened around the same time as the collapse into anarchy of the Egyptian Old Kingdom, also a time of drought and famine.

In the more technical sections that follow, I have delved into all kinds of primary sources and academic articles to gather enough information to hypothesise what an archetypal Sumerian or Akkadian army was like and how it operated in battle. I expect that in reality every army was subtly unique, especially given the time span and geographical extent we are exploring. Some details that we might think were typical might have been specific to one conquering city rather than its defeated foes. The tactics and organisation of armies could have been as varied among the Sumerian city states as it was among the Archaic Greek or Italian Renaissance city states, within the possibilities of the age. Sumerian and Akkadian terms are both given in italics, and I have chosen not to put the Sumerian into capitals as is the convention in academic articles. The scribes who wrote about these armies used both languages.

HISTORY: SUMERIAN & AKKADIAN WARFARE PART 2 – ARMY ORGANISATION

Ancients wargaming expert Nigel Stillman provided a detailed account of Early Bronze age warfare and focused on military development in the region. Here, in part 2, Nigel explains how armies were raised and organised.

RAISING AN ARMY

The city and its surrounding territory, in other words the city state, was considered to be owned by the patron god of that city. If two cities went to war over land it was also a quarrel between their respective gods. Indeed the god would be consulted about whether or not to go to war or not. Also consulted was the council of elders. The elders would vote or agree on the matter, and perhaps they would have originally appointed the Lugal or war leader, before this position turned into hereditary kingship. Hereditary kingship was not the rule everywhere or at all times, since rulers could arise from various origins.

The entire resources of the city-state, or at least most of them including its manpower, were at the disposal of the city’s god and therefore also the Ensi (high priest governor) or the Lugal (king, warlord). Manpower could be conscripted on a rota basis for a period of state duty, which might take the form of labour or military service. The Lugal and his military scribes would select the best men from the levy for military service. These augmented the Lugal’s own household contingent, which amounted to the regular standing army of the city. Full time soldiers were called Aga-ush, whereas a less specific term for troops or levies including men doing work duty or militia duty was Erin.

The Aga-ush included high-ranking officers, unit leaders and various city guards as well as soldiers. These military specialists would form the core of the expanded army and train the militia recruits. Among the duties that could be assigned to Aga-ush soldiers, aside from fighting in battle, were patrolling the routes against raiders, acting as messengers and operating as sailors (or rowers?) of the transport ships. Ships were needed to transport armies up and down the Tigris and Euphrates or even across the Persian Gulf to Magan or Awan (to the east of Elam).

TACTICAL ORGANISATION OF AN ARMY

Over and over again the records refer to units of 10, 60, 600 or 5000 men. The Stela of the Vultures depicts the serried ranks of a Sumerian close formation infantry unit. This is often referred to as a ‘phalanx’ by analogy with the later similar formations of classical times. These soldiers appear to be in a column of six ranks and ten files, advancing with spears levelled towards the enemy. The ancient sculptor of the relief carving has tried hard in his composition to demonstrate that the spears are long enough for six ranks to protrude in front of the big shields carried by those at the front of the formation.

Maybe the Lugal Eannatum himself briefed the sculptor because he was proud of the methods of war that had brought him victory – future generations take note… this is how it’s done! Long spears are mentioned in the records that list weapons issued to troops. Therefore this may be a representation of the basic unit of a Sumerian army – a company of 60 soldiers. This calls to mind the Roman republican ‘maniple’ of 60 Legionaries and the Ancient Egyptian basic unit of 40 men depicted by model soldiers from an Old Kingdom tomb. Later on, the Egyptians and most other countries had a basic unit of 50 men, but the Sumerians favoured a Sexigismal numbering system alongside a decimal system.

The ranks of military officers known from the records indicate the hierarchy of military units. The Ugula was a sort of NCO who led a squad of 10 men. Six squads of ten made up the 60 man unit commanded by an Ugula geshda (commander-of-60). Several units of 60 made up a brigade of up to 600 men, commanded by a Nubanda. Larger units, such as the entire household troops of a king, numbered around 5000, commanded by a Shagina (general). This would have included brigades and companies of all kinds of troops- the Sumerian equivalent to a ‘legion’ perhaps.

A large army (texts indicate 10,000 or 20,000 for Akkadian or Ur empire armies) might have two or more such ‘divisions’ especially if representing the combined army of allied cities or an empire. A single city probably had a small army of up to 5000 including the full militia. The scribes would need a reliable military organisation in place so as to calculate rations and supplies and replenish units with recruits. The actual unit strengths would vary on campaign, of course.

How did the chariotry, or rather the battle-carts, fit into this organisation? The inscriptions of the war between Lagash and Umma may give a clue. When Umma was defeated in battle, 60 of the city’s elite troops were cornered as they retreated from pursuing Lagashites. They ran up against an irrigation canal and were caught, resulting in five heaps of slain Ummaites to feed the vultures upon the plain of the Gu-Edina: the contested land where the battle was fought. Most researchers regard these elite troops to be the battle-cart contingent of Umma. This might indicate that there were 60 battle-carts, perhaps representing ten squadrons of six vehicles or six squadrons of ten vehicles. A basic unit of 6 vehicles is found in later chariot organisation.

SUMMARY OF MILITARY ORGANISATION

- The individual soldier and the individual battlecart with its crew and team of 4 asses.

- Squad of 10 soldiers commanded by the Ugula

- Squadron of 6 battle-carts?

- Company of 60 soldiers commanded by the Ugula-of-60.

- Brigade of 60 battlecarts.

- Brigade or regiment of 600 soldiers commanded by the Nubanda.

- Division of 5000 soldiers commanded by the Shagina.

- The whole army commanded by the Lugal.

Let us indulge in some speculation. In a hypothetical brigade of 600 soldiers it might have been possible to have:

- A company of 60 foot soldiers equipped as shield-bearers for the front rank.

- Six companies of 60 infantry spearmen armed with long spears in six rank columns.

- A company of 60 infantry skirmishers armed with javelins.

- A company of 60 infantry archers or slingers.

- A company of 60 infantry armed with the hefty Gamlu battle-axe, probably as the guard of the

- This formation might be supported by a squadron of 6 battle-carts.

Alternatively, if there were a brigade of 600 spearman, for example, such a formation would still need to operate in sub-units of 60 to march, deploy and avoid confusion in battle. Standards were used by the Sumerians and Akkadians, and may have been used at various levels of unit organisation. Certainly there was an army standard, and probably divisional and brigade standards as well. Drums are often mentioned in texts, usually in connection with rituals, but would be ideal to help drill and manoeuvre serried ranks, as well as inspiring dread as the spear formation advanced towards the foe.

HISTORY: SUMERIAN & AKKADIAN WARFARE PART 3 – TROOP TYPES

Part 3 examines the different troop types available to armies of the age. If you’ve not already done so, check out part one and part two first.

THE TACTICAL ELEMENTS OF AN ARMY

Each powerful city-state, as well as the Akkadian kings, the Third Dynasty of Ur and outlying kingdoms such as Mari, Ebla and Elam, raised a variant of the same pattern of army, made up of similar tactical elements. In the Early Dynastic phase there may have been greater variation between the armies of different states, perhaps reflecting individual technical or tactical innovation. Strategic genius on the part of commanders such as Eannatum of Lagash or Sargon of Akkad must, at least in part, account for the victory of their cities over their rivals. Other cities may have been ultimately vanquished because their armies had been decimated by constant warfare, regardless of their strength or quality. From the evidence we can identify the troop types described below.

HOUSEHOLD TROOPS – ROYAL GUARD

The household troops of the Lugal, known as Shub Lugal or Aga Ush Lugal, formed the bodyguard of the king and the core of the army. I expect that this contingent would include the best of the main troop types in the army, especially foot guards with battle-axes, battle-carts and archers with composite bows. Elite soldiers usually had similar armour to leaders and commanders, such as the broad shoulder bands known later as tuttitu. From this inner core would be selected the unit commanders. Officers and commanders carried batons and ornate weapons as an insignia of rank, and they wore decorated helmets. Standard bearers were often priests.

CLOSE FORMATION INFANTRY SPEARMEN

The infantry spearmen were known as Lu-Geshshuker or Lu-Geshgida after the long shukergallum spear (nicknamed ‘big needle’) and the Sumerian word for a spear, geshgid. They wore various kinds of armour. This seems to have been standardised within each city-state since it would be made in the state workshops. Armour would therefore have functioned as a distinctive uniform for the majority of the city-state’s soldiers. Spearmen of Ur wore a long, enveloping ‘war-cape’ studded with copper discs, leaving both hands free to hold a spear, and making a shield unnecessary. Lagash spearmen wore long fleecy kilts and shoulder bands, and at least the front rankers carried big rectangular shields with nine bosses, presumably copper. Akkadian spearmen, depicted carrying their long spears in the elbow at the ‘secure pike’ posture known from 17th Century European drill manuals, also wore long kilts and shoulder bands.

All spearmen wore conical copper helmets rather like a medieval bascinet, and most carried a light axe as personal armament. Akkadian helmets, of which there were more designs, had leather aventails protecting the neck. In Akkadian and Third Dynasty Ur armies, huge ‘tower’ shield were still favoured and were made of reed or leather. Each soldier could have one hung from a shoulder strap, leaving both hands free to hold a long spear (as in near contemporary Minoan armies) or shields could be dispensed with in difficult terrain. Maybe the spearmen operated in a more open formation in these circumstances; relying only on their armour.

It is usually assumed that the spearmen were the majority troop type in most armies, including regular soldiers and militia, but since they were well equipped, and their formations required rudimentary drill and discipline as well as a stubborn unit coherency and determination in battle, it might be that they were a limited and precious contingent, rather like the hoplites of a small Greek city-state.

The records indicate that Sumerians had units of 60, 100 or 600 men, but the formation depicted on the Stele of the Vultures actually shows eleven soldiers, since the carving of the unit goes around the side as well as the front of the stela. There are actually more soldiers than you usually see in illustrations of this monument in books. Usually this is interpreted as a unit of 60 men plus an officer, but equally likely is that it depicts 60 spearmen as shown by the six pairs of arms gripping spears, and a front rank of 10 shield bearers walking in front of them. Since this would make a unit of 70 men, for which there are no references in documents, it might instead mean a unit of 100 men only 60 of which were spearmen, with 10 being shield bearers and the remaining 30 being skirmishers, or maybe axemen, archers and skirmishers in small detachments.

More probably, and much simpler, would be to have a unit of 60 shield bearers who could deploy along the front of six units of spearmen. It is clear from the defensive armament, as well as the evidence for slings and archery, that the close formation troops had to try and make progress against a hail of missiles. Once most of the distance to the main enemy force had been covered, and their skirmishers swept away, the shield bearers could retire to the rear of the formation, or discard shields to fight with hand weapons or maybe retain their shields to assist in shoving and pushing the opposing enemy close formation troops. The Sumerian methods of organisation thus allowed for a lot of tactical variation and flexibility.

INFANTRY BATTLE-AXE MEN

Infantry axemen armed with battleaxes were known as Lu-Durtaba. The type of axe carried was called a Gamlu. It had a long handle with a curve at one end where the hefty crescentic blade was fitted. For those who wonder if axemen like this were really used, I refer you to the commander Lipet-Istar, who is recorded as sending out a force made up of equal numbers of spearmen, archers and axemen. Such axemen wore shoulderband armour and helmets, but are not shown with shields. Tucked into each soldier’s belt is a useful missile weapon: a pair of throwsticks known as a waspum or dalush, onomatapaic words for a hefty boomerang or throwing club. These were shaped aerodynamically to hurtle towards a foe at short range rather like a tomahawk. There are several ways in which axemen could be used tactically in battle; these are:

- To hack through the enemy line of shieldbearers.

- The hack off the long spear shafts of the enemy spearmen.

- To set upon stranded enemy battle-carts.

- To hack into the midst of the enemy formation to snatch the standard or strike down the leader.

- On campaign, to make a way through scrub for chariots and close formation troops.

- In siege-work, against gates and ladders, and against assault boats in actions on the Tigris or Euphrates.

INFANTRY ARCHERS

Infantry archers were known has Lu-Geshban. These appear on the Stela commemorating the campaign of the Akkadian king Naram-Sin against the Lullubi tribe in the Zagros Mountains. They would have proven very useful on steep, wooded slopes against barely armoured foes armed with javelins or bows. Archers sometimes wore helmets and armour. An archer depicted in what may be a siege action found at Mari, is shown wearing a broad studded band over one shoulder. He is behind his commander who holds a huge, curved reed pavise, and is shooting at a high angle with a recurved composite bow. In battle against Umma in the fields of the Gu-Edina, Eannatum of Lagash was wounded by an arrow, which he heroically broke off and continued fighting.

BATTLE-CARTS – EARLY CHARIOTRY

Chariotry, at this time being various designs of four or two wheeled battle-carts yoked to four wild asses, were known as Gishgigir. The two wheeled types, referred to as straddle and platform carts depending on whether the single crewman sat astride a saddle or stood on a platform, are often thought to be command vehicles. However, there is no reason why they might not be used just like the other battle-carts. The wheels of these vehicles are of solid wooden tripartite construction, with studded rims or leather tyres. The main feature is the upright cleft shield protecting the crew. The vehicle was probably constructed of wickerwork and a bent wood frame covered with leather. The four-wheeled battle-carts carried two crewmen, armed and armoured in the same way as elite soldiers. On the standard of Ur, a studded cape may be seen draped over the back of a battle-cart. The weaponry of the crew included a good supply of javelins carried in a quiver hung on the battle-cart, and a hefty mace or axe.

Battle-carts are shown charging, or rather pursuing, on the Standard of Ur. Each battle-cart is shown with the asses increasing their pace – from walk, to trot or canter and then to gallop. They trample fallen foemen while one crewman holds the reigns and the other hurls javelins. Asses are referred to frequently in records for pulling battle-carts and there were various types. It is thought that the wild asses, known as onagers, were rounded up on the Mesopotamian steppe (the Jazira) and harnessed to the battle-carts. It is also possible that mules, asses and possibly steppe ponies or small horses from Iran (the Anshe-zizi or Anshe kurru ‘foreign ass’) were used if available. The last of these are shown pulling the much later Elamite four-crew chariot. The ass team were protected by fabric or leather frontal armour.

Reconstructing the design of these chariots is greatly helped by looking at the many pottery and bronze models that have been found. These show in three dimensions what is often distorted by ancient efforts at perspective in two-dimensional scenes. Also, actual battle-carts have been excavated from burials at Kish and other sites, especially in the Caucasus region and the Eurasian steppes. These vehicles were in widespread use and appear on cylinder seals from Anatolia. The wheel types are known as far away as Europe. Many years ago a Sumerian chariot was reconstructed and tested as experimental archaeology for a television program. It was found to be reasonably fast, the asses were manageable and it had a wide turning arc.

SKIRMISHERS AND LIGHT TROOPS

Skirmishers and light troops armed with slings, javelins and simple bows were probably provided by the conscripted militia. Finds of masses of sling stones at the site of a sacked city of the Uruk period, indicate that slings were important at least in siege warfare. The capes and big shields of the spearmen were intended to defend them from something. Probably this was missiles, and most likely a hail of sling-stones that they had to advance against. Sling-stones strike with much force, but Sumerian armour types would be effective. Skirmishers were likened to irritating swarms of stinging flies, gnats and insects.

TRIBAL AUXILIARIES

Foreign auxiliaries included warriors from the nomadic Amorite tribes of the desert, known as Martu, that were living at this time in northern Mesopotamia and regions to the west. They were fierce and armed with a variety of weapons, as well as being skillful in tribal warfare, but they tended to be treacherous. A bodyguard of such troops, though useful and intimidating, might overthrow the king and put their own chieftain in charge. If a tribe was allowed to settle or graze their herds within the territory of a city-state, then the usual tribute, apart from animals, wool and hides, was to provide warriors for military service. Amorite troops were a major part of the army of Ebla. The Guti tribe of the Zagros Mountains also provided auxiliaries. Usually these were armed with bows, axes and javelins. A mercenary or allied contingent might be obtained from Elam, a much more civilised land that was governed from the city of Susa and ruled by Elamite kings or sometimes an Akkadian governor.

Elamites could be a variant of any of the troops known from Mesopotamia, but the scanty evidence indicates armies included many archers armed with composite bows and wearing horned helmets. At this time, few of these tribal warriors used shields. Guti and Lullubi warriors wore a long hide robe fastened at one shoulder, rather like that worn by early Libyan warriors. Throwsticks were a favourite weapon of the Amorite nomad warriors and Gutian highlanders, in addition to short spears, bows, light axes, javelins, slings and daggers. Records from Ebla tell us that Amorites, being skilful metal smelters, made highly prized daggers and sickle swords.

ALLIES

In the Early Dynastic period, the region around Kish and to the North was home to the Akkadians. It is often thought that the Akkadians made greater use of the composite bow than did the Sumerians, and this was exploited by Sargon to gain the upper hand over his rivals. Most evidence suggests that armies from Akkad and Kish, which lay within the same area, were organised just like those in Sumer. Perhaps they were stronger in battle-carts, since they might have better access to regions where the wild asses roamed. Far to the south, across the Persian Gulf but accessible also by marching overland, were the regions of Dilmun (Bahrain) and Magan. The Akkadian king Manishtushu conquered these lands. Here it ws possible to trade with merchants from the far away Indus civilisation, known as Melukhkha. The warriors encountered here lived in a copper-producing region, and were armed with spears and an early form of sword.

In the opposite direction, to the northwest, were the Hattian kingdoms, ancestors of the Hittites. Their armies included spearmen, axemen and battle-carts. Troy II was a mighty city at this time, but we know little of its military power as yet. The city of Ebla ruled a large area stretching across Upper Mesopotamia from Hamazi and Ashur in the east as far as Byblos and Canaan in the west. Ebla was a great rival of Mari. Eventually both cities would fall to the king of Akkad. Ebla recruited warriors from the Amorite tribes of this region, and sent a request to the allied city of Hamazi in distant Iran saying send me good mercenaries!

HISTORY: SUMERIAN & AKKADIAN WARFARE PART 4 – BATTLES

Ancients wargaming expert Nigel Stillman continues his detailed account of Early Bronze age warfare. Part 4 completes Nigel’s article with a look at how battles were actually fought.

HOW TO FIGHT A BATTLE WITH THE SUMERIAN OR AKKADIAN ARMY

SURVEY THE BATTLEFIELD

First the commander and his generals would survey the battlefield. It would be difficult to find a high point on the plains of Sumer. In the highlands, the foe might be lurking higher upslope than the invaders! Commanders riding on battle-carts or other chariots would gain some height, possibly helping their own troops to recognise them above the clouds of dust. In a battle between Lagash and Umma, the Ummaites are said to have deployed their vanguard on a feature called ‘Black Dog Hill’. Scouting ahead with light troops to secure such advantageous positions would be important. Shulgi, the mightiest of the kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur says; ‘when I set off for battle…I go ahead of the main force of my army and I clear the ground for my scouts. I have a real passion for weapons! Not only do I carry a javelin and spear; I also know how to hurl slingstones with the sling. The clay slingshot ….fly like a violent hailstorm…I do not let them miss!.

The records of the border war between Lagash and Umma, which was fought over the stretch of disputed semi-desert known as the Gu-Edina, gives details of the terrain futures. As the war progressed each side added more features to the terrain in their efforts to demarcate the border. A few extracts from the texts indicate the sort of scenery among which Sumerian armies clashed on the plains of Sumer. Mesalim, king of Kish (who initially arbitrated the border) measured the field and erected a stela. Later, Ush, ruler of Umma, arrogantly pulled out the stela and marched into the plain of Lagash. Umma was defeated and a great burial mound raised over the slain enemy in the plain.

The border was remade and the irrigation channel, called the Inun-canal, was extended into the area. The stela was restored and a new one set up. Three shrines to the gods were built upon the levee raised to demarcate the border. Along one edge of the battle-zone the River Tigris flowed near the town of Girsu. There were cultivated fields of barley and irrigation ditches around here. Umma claimed some of these irrigation ditches and diverted the water, breaching the levee, but Lagash responded by extending an irrigation canal from the Tigris to the Inun-canal, and the levee and its shrines were reinforced with stone. Would you want to fight with battle-carts in terrain criss-crossed with ditches like this? In a subsequent battle it appears that Umma’s elite brigade of 60 battlecarts was cornered against a canal while trying to retreat and wiped out, resulting in five more burial mounds upon the plain.

Against the Guti highlanders, and also on campaign in Anatolia, Akkadian armies of Sargon and Naram-Sin marched with their formations of close order spearmen into high, forested mountains. They appear to have been successful. For campaigns up the Tigris and Euphrates and over the sea to Magan (Oman) embarkation and disembarkation of a large army from many big boats, would be required.

DEPLOY THE ARMY

The Stela of the Vultures likens the battle to the city god casting a huge fishing net over the foe- the battle-net. The god is depicted with vanquished foemen trapped in a net like fish and bopping them on their protruding heads with his mace. Maybe this heroic image was suggested by the view of the various sub-units of the army drawn up for battle. With blocks of spearmen, perhaps in a chequerboard formation, connected by lines of skirmishers, the deployment might look like a huge net advancing to envelope the enemy army.

SKIRMISH

The main close combat troops were issued with armour or big shields to protect them against the hail of missiles that would inevitably be hurled at them by enemy skirmishers as they advanced. These skirmishers would attempt to wear them down, tire them out, distract them, and screen their own close combat troops. It would be a test of discipline to keep up a relentless advance in the face of this ‘hailstorm of slingstones’ as the Sumerian texts call it. Your own skirmishers could be sent forward to try and chase them off, and shield bearers could advance in front of unshielded spearmen. Another option would be to unleash a few battle-carts to chase away enemy light troops. The battle-carts could use a short spurt of speed directly ahead to panic the skirmishers into taking rapid evasive action or be trampled, assuming that the battle-carts, which had frontal protection and a big upright frontal shield, could survive the missiles.

THE CLASH OF CLOSE COMBAT

Eventually, the close combat formations of spearmen would crash into each other. This might vary from a surge of impetus or a slow motion thrusting and shoving, until one side lost cohesion and gave way. A lot would depend on the discipline, stubbornness and determination of the soldiers to decide who defeated whom. Units on both sides would recoil or push forward, creating opportunities for other units to crash into the flanks of the foe to help out hard-pressed comrades. Here the handy 60 man units would prove useful, as would the use of small units of axemen. If gaps appeared in the enemy battle line as units fell back or fled; the battle-carts could trundle through and trample the fleeing foe, preventing them from rallying to make another stand. Victory would usually go to the best disciplined, best trained, bravest and most determined side.

UNLEASH THE BATTLE-CARTS

On open ground, such as desert margins, a force of battle-carts could be deployed on the flanks to be sent around the enemy army. They might, of course be opposed by enemy battle-carts, light troops, tribal auxiliaries or skirmishers. Light troops might be swept away or trampled, but enemy chariots would result in a confused melee. Here supporting light troops might tip the balance. Against steady close-formation spearmen, the battle-carts would have doubtful chance if they charged directly; but might ride past hurling javelins. The spearmen would not dare to move while under such attack. It is possible that the long-spear formation was actually devised to deter chariots as much as to gain advantage over enemy close-combat infantry.

At the moment in the battle when the enemy formations had taken a beating and were falling back in disorder; the battle-carts would be unleashed in a mass attack. They would pursue; overtake, strike down, trample and chase the fleeing foe, preventing any chance of them rallying and possibly even pursuing them to the gates of their city. The close-formation spearmen, having done their work in the grinding hand-to-hand combat, would be far too tired and encumbered to pursue the foe. If the enemy were allowed to get away, the battle would be indecisive and a rallying enemy army might even manage to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. Only relentless pursuit and heavy losses resulting in heaps of slain to feast the vultures would make sure that the rival city knew it was beaten. Kingship would pass to the victor; the crown awarded by the elite troops of the battle-carts, even if hard won by the sweat and blood of the citizen militia.

Further Reading

- Van De Mieroop, A History of the Ancient Near East, Blackwell, 2007.

- Stillman & N.Tallis, Armies of the Ancient Near East, WRG, 1984.

- Kriwaczek, Babylon; Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilisation, Atlantic, 2010.

- Yadin, The Art of Warfare in Biblical Lands, London, 1963.

- Pettinato, Ebla,London, 1991.

- Internet; sumerianshakespear

- Lafont, The Army of the Kings of Ur: The Textual Evidence, Paris, 2009.

HISTORY: AKKADIAN EMPIRE

The Akkadian Empire was founded by Sargon the Great of Akkad in c. 2334 BCE and lasted little over a century. The original city-state of Akkad was located somewhere in northern Sumer but has yet to be found. However, Akkadian speakers were present in the earlier first Dynasty of Kish at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BCE.

In c.2271 BCE Sargon routed the Sumerian forces of Lugal-Zage-Si of the city-state of Umma at the Battle of Uruk and annexed the rest of Sumer. He went on to conquer lands as far west as Syria and Canaan and reached the Mediterranean Sea. He fought the Hattians (proto-Hittites) in Anatolia and subjugated the mountainous tribes of Subartu/Assyria in the north and the Gutians in the east. In the south-east he defeated the Elamites and even reached as far south as the early Arabian state of Magan.

Sargon was succeeded by his sons, firstly Rimush and then Manishtusu who managed to maintain the empire from various revolts. Manishtusu’s son, Naram-Sin went on to expand the empire further and battle against the Zagros highlander tribes such as the Lullubi and Gutians.

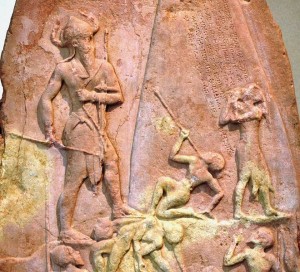

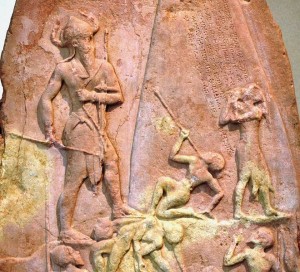

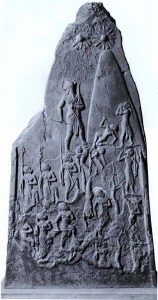

The famous “Victory Stele of Naram-Sin” (as shown in the image below) depicts his campaign against the Lullubi. Naram-Sin also fought against the early Hurrian tribes in the north-west, Hattians in Anatolia and, like his predesessors, the state of Magan.

The last Kings of Akkad reigned over a period of decline until in c.2154 BCE the empire collapsed after invading Gutian Highlander tribes from the Zagros Mountains took control. For a hundred years the region was controlled by the Hurrians in the north and Gutians in the south.

The “barbarian” period eventually came to an end with the establishment of the 3rd Dynasty of Ur by the Sumerian King, Ur-Nammu, in c.2112 BCE, who ejected the Gutians and united the area again.

HISTORY: NEO-SUMERIANS AND SUCCESSORS

Following the collapse of the Akkadian Empire about 2100BC there was a period of disorder during which the country was ruled or at least dominated by the Gutians. No-one knows exactly who the Gutians of this period were (the same name was later used to described other peoples who lived in the Zagros Mountains much later). But one thing is for sure – they were barbarians! They overran the ordered, settled and intensely irrigated lands of the Akkadian Empire. In many cases they installed their own Kings and in others they accepted the subjugation of the locals and no doubt extorted what they wanted by way of tribute. The Gutians came from the Zagros Mountains and were a savage, illiterate hill-folk, so it is likely that populations declined generally and many settlements were abandoned during this time of anarchy and woe. It’s not altogether clear how long the reign of the Gutians lasted – and the chances are that some Gutian rulers hung on even once the power of the invaders had been substantially broken – but a period of about a hundred years may be envisaged.

Despite the predations of the Gutians civilisation was not entirely destroyed and some cities evidently continued to thrive – probably whilst paying tributes to the Gutian Kings. Resistance to the Gutians may have been more widespread that we know, but eventually Utu-Hengal of Uruk and Ur-Nammu of Ur succeeded in defeating the Gutian King Tirigan and regaining control of Sumeria. From this beginning arose a reborn Sumerian Empire that we call the Third Dynasty of Ur, often written UrIII, and also known as the Neo-Sumerian Empire. After the death of Utu-Hengal, Ur-Nammu began the reconquest of Sumeria, and under his son Shulgi the Sumerians re-established their rule over much of the area previously contolled by the Akkadian Empire.

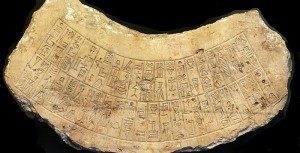

|

| Stele of Ur-Nammu – the first King of the Third Dynasty of Ur. |

The Neo-Sumerian period lasted for about a hundred years. It is sometimes referred to a renaissance in Sumerian civilisation and in particular the old Sumerian language. It was certainly a period of intense activity, with the reconstruction of roads and cities, and the reestablishment of order over the countryside. It was during this time that Ur-Nammu began the construction of the Great Ziggurat of Ur, completed by his son Shulgi.

|

| Reconstruction of Great Ziggurat of Ur began by Ur-Nammu. Dedicated to the Moon God Nanna the patron deity of Ur. Completed by Ur-Nammu’s son Shulgi. |

Here is a list of the Kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur according to the most commonly used chronology.

Under Shulgi and his successors the Sumerians continued to campaign to the east and north. No doubt they fought partly to gain subject territories, which would have garrisons and military governors installed, and partly simply to forestall raiding and aggression by enemies into Sumeria itself. Shulgi’s early campaigns lasted for more than twenty five years and extended the empire northwards into what would become Assyria, beginning with the defeat of the city of Der and progressing northwards as far as Urbilum to the north of Ashur. To the east he fought in Elam and Anshan. His successors continued to campaign, but less actively.

We can gather a lot about the armies of the Neo-Sumerians from lists of provisions and weaponry supplied to garrisons throughout the land. From these we learn that the ordinary militia carried spears, and at least some carried the traditional large, rectangular shield. Troops of Amorite origin may have carried the distinctively shaped Amorite shield instead. Others, probably the professional soldiers, carried bows – of which there were two types, one described as the ‘complex’ bow. It’s not clear what this refers to, but it may represent an improvement in the form of a composite bow of some kind. The other kinds of troops are axemen or carry a mace (ges-tukul). At least one document presents these three types in equal numbers – one third of each comprising a force.

The true chariot was still some hundreds of years from full development, but records suggests that new equid types were making an appearance – the ‘foreign ass’ as horses were at first called. The traditional battle-car was supplemented by various kinds of two-wheeled proto-chariot – the warrior now often carrying a bow rather than javelins. The names of many Neo-Sumerian commanders that come down to us include Elamites, Hurrians, and Amorites as well as Akkadians and Sumerians, so it was obviously a time of considerable cultural exchange and movement. Although we call this period Neo-Sumerian, it would be wrong to think of it as backward looking, the Kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur ruled a land that was at the forefront of military developments.

The Neo-Sumerians eventually succumbed to a resurgent Elam together with increased pressure from Amorite tribes to the northwest. One Neo-Sumerian King actually built a defensive wall between the Tigris and Euphrates to try and hold the Amorites at bay – but it was to no avail.

In Hail Caesar the Sumer and Akkad list provides the basis for an army of this period; however, we might make allowance for what we know of the increased importance of the bow in warfare, and developments of the chariot from the earlier battle-car. Although these developments rightly belong to the first quarter of the new millennium, technology does not stand still – and it is entirely reasonable to reflect this in the army list. Therefore, here is a revised army list specifically for the Third Dynasty of Ur, representing the forces of Ur and of contemporary cities of comparable status.

THIRD DYNASTY OF UR ARMY LIST

(army list for use with WG Hail Caesar)

| THIRD DYNASTY OF UR – 21th Century BC | |||||||||

| Chariots up to 25% | Up to a quarter of the units in the army can comprise chariots. | ||||||||

| Infantry 75%+ | At least three quarters of the units in the army must comprise infantry other than skirmishers. | ||||||||

| Sumerian spearmen 25%+ of infantry | At least a quarter of the non-skirmisher infantry units must be either Sumerian medium infantry with long spears. | ||||||||

| Sumerian bowmen 25%+ of infantry | At least a quarter of the non-skirmisher infantry units must be Sumerian bowmen.. | ||||||||

| Sumerian Axemen/Macemen and Royal Guard 25%+ of infantry | At least a quarter of the non-skirmisher infantry units must be Sumerian Axemen/Macemen or Royal Guard. | ||||||||

| Divisions 4+ units. | Divisions must contain at least 4 units excluding skirmishers and must be led by a commander. | ||||||||

| Skirmishers per division 50% of infantry | Divisions may contain up to half as many skirmisher units as they contain non-skirmisher infantry. | ||||||||

| TROOP VALUES | |||||||||

| Type/stats | Combat | Morale Save | Stamina | Special | Points Value | ||||

| Clash | Sustained | Short | Long | ||||||

| Sumerian or medium infantry with long spear. | 6 | 6 | 3/0 | 0 | 5+ | 6 | 23 points per unit | ||

| Sumerian or medium infantry with double handed weapons | 7 | 6 | 2/0 | 0 | 5+ | 6 | 23 points per unit | ||

| Royal Guard medium infantry with double-handed weapons one unit maximum | 7 | 6 | 2/0 | 0 | 5+ | 6 | Tough Fighters | 24 points per unit | |

| Sumerian light infantry archers | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 20 points per unit | ||

| Skirmishers with javelins fielded as a small unit. | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 11 points per unit | ||

| Skirmishers with slings fielded as a small unit. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | Levy | 10 points per unit | |

| Amorite skirmishers with bows fielded as a small unit – up to one per Amorite warband | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 12 points per unit | ||

| Amorite medium infantry tribal warband with spears, javelins, bows. | 7 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 6+ | 6 | Wild Fighters | 25 points per unit | |

| Gutian light infantry with double-handed weapons and throw sticks fielded as a small unit. | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 6+ | 4 | Marauders | 17 points per unit | |

| Elamite light infantry archers fielded as a small unit. | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | Marauders | 18 points per unit | |

| Proto- Chariots light chariots with javelin armed crew | 8 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 4+ | 6 | 28points per unit | ||

| Proto- Chariots light chariots with bow armed crew | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 4+ | 6 | 30 points per unit | ||

| Commanders | 1 Commander must be provided per division. All commanders including general have Leadership 8. | Free | |||||||

| | |||||||||

PART II

Early Desert Nomads

The fertile lands of Mesopotamia, the coastal Levant, and Egypt were surrounded and partly separated by arid semi-desert or dry steppe regions. These included the Syrian Desert and the northern portion of the Arabian Peninsula. Over thousands of years these marginal lands were always the first to be affected by cyclical periods of wet or dry climate. These same climatic cycles also had an impact upon the civilisations of Sumer, Egypt and the Levant (the eastern coast of the Mediterranean), occasionally affecting harvests and leading to starvation, disease and political instability.

However, these changes were even more devastating in marginal and mostly arid regions, such as the lands west of the Euphrates – which the Sumerians called the Martu lands. In Sumerian records the Martu lands included not only the Syrian Desert, but also the whole of Canaan, regions which the scribes populated with wandering tribes opf nomadic herders. The Egyptians referred to these desert dwellers as Aamu, whilst the Akkadians called them Amarru, and – thanks to the bible – they are known to us as Amorites. The Amorites were numerous and, when they first appear in the historical record, they are associated with the mountainous region of Jebel Bishri in Syria – known as the Mountain of the Amorites.

This Egyptian tomb painting is from about 1900BC and shows a group of Amorites – the hieroglyphs above the figures leading the ibex/goats identify them as Aamu. Note the contrast between the bearded Amorites and their multi-coloured clothing and the Egyptian leading them. In the bottom register we see women, children and what could be a mobile forge carried by a donkey. Tomb of Khnumhotep at Beni Hassan 12th Dynasty.

The Amorites were a perpetual nuisance in Mesopotamia where tempting pasture was relatively abundant. During times of hardship the Amorites would try to move eastward and take over territories that were at least nominally part of Akkadia or Sumeria. Akkadian and Sumerian Kings would often try and drive these nomads away, even going as far as to erect a wall between the Tigris and Euphrates to keep them out, but it was to little avail. Eventually the Amorites settled within Mesopotamia, and following the fall of the Akkadian Empire they set-up their own Kingdoms or took over many of the old Akkadian and Sumerian settlements. Ironically, these assimilated Amorites subsequently suffered the same problems from nomadic Amorites that had afflicted the Akkadians, which just goes to show that the Amorites were not really a nation but disparate groups of tribes and nomadic communities.

Warfare was undoubtedly endemic amongst these tribes, as is the case in all societies that lack central government or a sense of unifying political identity. But they were tough warriors, probably naturally inured to hardship because of their life-style, and ready to take what they needed from others in order to survive. They appear as mercenaries or subject troops in Akkadian and Sumerian armies, for example, and as raiders and bandits in their own right. During the early second millennium BC new names appear that described nomadic groups or desert raiders – and these would have been essentially similar in appearance to the earlier Amorites. Amongst them are wandering bands of Habiru – who plagued the Levant region and Egypt – and Arabian tribes such as those known as Shasu in later Bronze Age Egyptian records.

The Warlord Games Desert Nomads Range represents the fighting forces of these early Amorite raiders, mercenaries and tribute troops – and are ideal for representing any of the culturally comparable nomads from the entire region including early Arabs and Habiru.

These figures can be used to build armies of the ‘Donkey-Nomad’ or early Bedouin tribes of the Arabian Desert and Dry-Steppe regions surrounding Mesopotamia, Canaan and Syria during the Early and Middle Bronze Age. In Mesopotamia they were known variously, by the Sumerians as Martu, by the Akkadians as Amurru and by Neo-Sumerians as Tidnumites. They are more popularly known from the Bible as Amorites. They gradually assimilated with, and ultimately overran, the City-States of Mesopotamia and Syria at the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age. However, many of the tribes still remained nomadic and continued to war with, or ally with, the susequently settled Amorite City-States.

They were also enemies of Old and Middle Kingdom Egypt, where they were known variously as Aamu, ‘Asiatics, ‘Sand-Dwellers’ or ‘Easteners’. It is also widely believed that the Hyksos or ‘foreign rulers’, who invaded Egypt at the end of the Middle Bronze Age, were Amorites. Hence, Hyksos armies can be built using figures from this range, combined with figures from the Amorite Kingdoms range.

The Shieldless Javelinmen, Archers and Slingers can be used for later Bedouin Nomad sub-groups such as the Hanu and Sutu, who would have dressed simliarly, as would the Habiru/Apiru (possibly early Hebrews).

However, figures for the Nomadic tribes and Early Hebrews of the Late Bronze Age will form a later separate range. The ‘Camel-Nomad’ tribes of the Later Aramaeans, Midianites, Amalekites and early or proto-Arabs will form another range within the future Iron Age section.

PART III

HIGHLAND TRIBES OF THE ZAGROS MOUNTAINS – GUTIANS AND LULLUBI

As is so often the case with the enemies of the Akkadians what we know of the fierce hill tribes of the Zagros and Taurus mountains is what the Akkadians care to tell us of them. In the case of the Lullubi, this information comes from the records of several Akkadian Kings, most significantly the stele of Naram Sin which pictures the great man himself casting down the defeated foe!

|

| Naram Sin defeats the Lullubi – about 2230BC |

The Lullubi came from a distant region in the north-east of the Zagros mountains, most likely the part of the Lower Zab valley where the Iraqi city of Halabjha is situated today. To the south of them, and occupying a much broader territory within the central Zagros mountains, lived the far more numerous Gutians. Once more we only have the records of their enemies to tell us what these chaps were like – and needless to say they were a bunch of uncouth and violent savages who were disrespectful of the gods to boot!

Naram Sin not only sorted out those pesky Lullubi, he also campaigned against the Gutians, defeating their king Gula’am. Naram Sin’s son Shar-Kali-Sharri also fought several campaigns against the Gutians, enjoying such success that he went so far as to claim that, ‘the yoke was imposed upon Gutium’. Brave words indeed considering that within a few decades the Akkadian Empire had been overrun by those same Gutians. Thus began a period of untold misery and national decline that would endure until the invaders were eventually expelled upon the tide of the Neo-Sumerian renaissance. Getting rid of the Gutians proved no easy task: Ur Nammu the first King of the UrIII period was killed in battle against the Gutians, and his son Shulgi continued the struggle in a series of campaigns throughout his reign.

Over time the names Lullubi and Gutian became a little blurred in terms of their exact designation, and began to be used rather indiscriminately for any barbarous highlander. During the many centuries we are talking about, it is very likely these people moved about a good deal and eventually intermingled with and were either absorbed or absorbed by their neighbours. All that we have left to tell their story are a few personal names to suggest that they were distinct non-indo-european peoples who were – at least to start with – unrelated to the Semitic settlers of the plains, neighbouring peoples such as the Hurrians to the north, or – indeed – each other. No doubt in later times they coalesced or were subsumed into more recent highland groups – not least the Kassites who were to descend from the mountains and take control of Babylonia during the Late Bronze Age.

In terms of Hail Caesar a Gutian raiding force can only be speculatively reconstructed at best. On this basis I have put together a list that is contemporary with the Akkad and Sumer list from Hail Caesar Biblical Armies, and the Third Dynasty of Ur List included in a previous posting. I have included proto-chariots (at least one Gutian King attended battle riding a chariot) to give the list a little variety, but otherwise the list is largely made up of light infantry and skirmishers. The same list would enable the Lullubi or any Early Bronze Age highlander force from the region to be assembled with a fair degree of credibility.

GUTIAN RAIDERS 25-21ST CENTURY BC ARMY LIST

(army list for use with WG Hail Caesar)

| GUTIAN RAIDERS 25-21ST CENTURY BC | |||||||||

| Chariots up to one unit | Up to one unit in the army can be chariots. | ||||||||

| Infantry – 50%+ | At least half of the units in the army must comprise infantry other than skirmishers. | ||||||||

| Divisions 2+ units | Divisions must contain at least 2 units excluding skirmishers and must be led by a commander. | ||||||||

| Skirmishers per division 100% of infantry | Divisions may contain up to as many skirmisher units as they contain non-skirmisher infantry. | ||||||||

| TROOP VALUES | |||||||||

| Type/stats | Combat | Morale Save | Stamina | Special | Points Value | ||||

| Clash | Sustained | Short | Long | ||||||

| Skirmishers with javelins fielded as a small unit. | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 11 points per unit | ||

| Skirmishers with slings fielded as a small unit. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 11 points per unit | ||

| Gutian tribal warband with spears, javelins and throw sticks. | 7 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 6+ | 6 | Wild Fighters | 25 points per unit | |

| Gutian light infantry with double-handed weapons (axes) and throw sticks and/or javelins fielded as a small unit. | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 6+ | 4 | Marauders | 17 points per unit | |

| Gutian light infantry archers fielded as a small unit. Up to 1 unit maximum. | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | Marauders | 18 points per unit | |

| Proto- Chariots light chariots with javelin armed crew. Up to 1 unit maximum. | 8 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 4+ | 6 | 28 points per unit | ||

| Commanders | 1 Commander must be provided per division. All commanders including general have Leadership 8. | Free | |||||||

PART IV

HISTORY: BATTLES OF HAMMURABI

PART 1 – THE RISE OF BABYLON

Bronze Age expert Nigel Stillman returns with a new series of articles on King Hammurabi of Babylon, his wars against neighbouring city-states including the Elamites and his final defeat at the hands of the Hittites.

.

RISE OF BABYLON

The rise of Babylonia and Assyria can be traced back to the age of Amorite warlords. In 1808 BC in Upper Mesopotamia, known then as Subartu, the Amorite warlord Shamshi-Adad I seized the throne of the old city of Ashur on the Tigris, in the heartland of Assyria. In 1792 BC in Lower Mesopotamia, known as Sumer and Akkad, an Amorite king ruled in Babylon. Situated in the ‘waist’ of Mesopotamia, where Tigris and Euphrates rivers flow closest together, it was an important strategic location, not far from Kish, Agade, Ctesiphon and modern Baghdad, all centres of imperial power at one time or another.

Babylon was not yet a powerful city, while the rival cities of Isin and Larsa fought for supremacy. A third mighty warlord was not destined to be founder of a great kingdom. This was the Amorite Zimri-Lim, who regained the throne of Mari on the Euphrates in 1776 BC. He battled against Shamshi-Adad, was an ally of Hammurabi, and ruled over a vast area that would one day become Syria, but was ultimately vanquished by Hammurabi and his realm was taken over by the Hurrians. The conquests of Hammurabi resulted in the unification of Mesopotamia into the kingdom of Babylonia.

These warrior kings were descended from Amorite nomad chieftains who lived in tents. Their subjects were both Akkadians and Amorite tribesmen. The Amorites had come from the arid steppes and deserts of Upper Mesopotamia and regions to the West. They had once provided mercenary warriors to the kingdom of Ebla. Later, their migrations into Mesopotamia created such a threat to the Kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur that they built a wall between the Tigris and Euphrates to curb their incursions. It failed, and as the Sumerian Empire collapsed amid famine, Amorite and Elamite mercenary warlords took over.

After a few generations, the descendants of tribal chiefs had absorbed a great deal of Akkadian culture, but kept their Amorite tribal connections and fashioned their armies according to the methods of Amorite tribal warfare; which had proved effective after all.

.

CAMPAIGN REPORTS

We know much about this period due to the discovery of several archives of clay tablets inscribed with the cuneiform script, especially those found at Mari. These are written in the Akkadian language, the standard scribal language for letters, diplomacy and administration, while Sumerian was reserved for religious texts. The Amorites spoke a related Semitic language and so Amorite words appear in the Akkadian texts. All of these languages are ancestral to Hebrew and Arabic and thus the name of a weapon or a military term in a text of this time is often the ancestor of a later Biblical or even Medieval Arabic term.

Many clay tablets are letters, which were dictated to scribes who sat beside their king as he spoke. These amazing documents record history being made as it happened, with all the comments and flourish of the agitated ruler, general or spy as he dictated to his scribe. Consequently they are full of details of campaigns, skirmishes, armies and battles as well as intrigue and espionage. They are unlike the carefully edited and bombastic royal inscriptions usually associated with ancient empires.

Here is an example from the Mari archive in which Zimri-Lim’s general, Ibalpiel reports back from Babylon where he commands the Mari ally contingent supporting Hammurabi against Elam:

“To My Lord from Ibalpiel your servant: Hammurabi said this to me: ‘a heavy armed force went out to attack the enemy column, but no suitable place could be found, so the force returned empty-handed and the enemy column is proceeding in good order without panic. Now send out a light armed force to raid the column and capture prisoners for interrogation.’ That’s Hammurabi’s orders. So I am sending Sakirum with 300 troops to Shabazum and the troops I have sent are 150 Hana, 50 Suhu and 100 troops from the Euphrates valley and there are also 300 troops from Babylon. In the vanguard of My Lord’s troops goes Ilunasir the seer, My Lord’s subject and a Babylonian seer goes with the troops of Babylon. These 600 troops are based at Shabazum and the seer consults the omens. When the omens are favourable; 150 go out and 150 come in. May My Lord be informed. My Lord’s troops are well.”

The Mari archive includes texts from the time of Shamshi-Adad I, when his son Yashmakhaddu governed Mari. This was before Zimri-Lim defeated Yashmakhaddu and regained the throne of Mari. Here Shamshi-Adad advises his young son how to raise an army quickly to besiege the town of Nurrugum:

“General Yarimaddu told me that he had inspected the Khana tribesmen and picked 2000 to go on the campaign with you and their names are noted on a tablet. Choose for yourself the 2000 Khana who will march with you and the 3000 already picked. Have Layum and your other advisors hear this tablet and help you decide. A tally of your men for military service is long overdue and as you can’t do it now, do it on your return. Until then, replace only deserters, missing and dead. Conscript 1000 men between the two towns and 1000 Khana, 600 Uprapu, Yarikhu and Amanu. Round up a further 200 and 300 men wherever you can and make a unit of 500. You will only need 1000 of your household troops. Then you will have 10,000 troops. I will send 10,000 landsmen (Ashurite territorial soldiers) who form a strong and well-equipped contingent. I have also sent word to Eshnunna for 6000 men to come up from there. Together making up 20,000 we have a strong army!”

A report from a commander of a Mari contingent on campaign in Subartu supporting local kings records a battle. On one side was Akinamar, ally of the King of Kurda, the king of Kahat, the king of Tilla and a warlord Askuraddu who had ‘no throne’. On the other side were the forces of Huziran, a pretender to the throne of Hazzikhannum, with allies from Shubat-Enlil, Andraig and Mari. The Mari contingent led by Ishri-Addu advanced. The enemy responded by taking up a strong position at Mariyatum. The Marians surrounded them, but lacked enough troops to attack.

So Huziran’s brigade of 500 men went to support them; but next day the enemy (originally 1500) had been reinforced by the Kahat brigade of 700 men and more Tillan troops, who broke the siege. The Kurdites got out of Mariyatum. On their retreat, the Kahat force was pursued by 100 men of Ishri-addu and 150 of Huziran’s men intending to overtake and ambush them. Near Pardu 250 men overtook them unnoticed and waited between Kahat and Pardu, then attacked. In a brisk battle the enemy were routed, killing 6, while every attacker captured one enemy each, for no losses. The report ends;” the Kahatu were well beaten, the servants of my lord were victorious; it was a good action by Ishri-Addu!”

We often find that the texts do not tell us everything we might like to know. We have a reply from the commander Habdumalik; “Why should I send my lord a long report? The orders are too detailed to be written on a single tablet, so I decided to send only a brief outline of the plan.” Also – every military archive has one – a request for socks, boots, underwear or beer! Here is the one from Mari; “Yamsum to Shunuhruhah: You asked me look for a good pair of boots to send you. I found some but they were too small. Send me an outline of your feet and I shall have good boots made for you.”

The warfare of the age can be described using the translations of these texts, which are very evocative and entertaining. Rather than quoting actual texts, I shall use them as inspiration for the story, with the dialogue based on the cuneiform reports or the gist of them, as is often done for TV dramatisations of episodes in World War two for example, where actors speak lines based on real wartime letters and despatches. Let’s first place this narrative in its time and place and provide some background information and a brief timeline of the key events according to the Middle Chronology currently favoured by researchers of Ancient Mesopotamia.

Beware that different areas of scholarship opt for different chronological schemes that do not always synchronise very well. Dates for this period are approximate; expect them to be revised by anything from a decade to a century according to new discoveries. I think this will tend to push the dates later rather than earlier. Fortunately, due to the amount of information we have interconnecting the various kingdoms, the period holds together as a block of time. As to names I shall only hyphenate them where it helps pronunciation.

.

KEY EVENTS

2000 BC – Fall of Ur. End of Sumerian empire. City of Isin holds out, under Ishbi-Erra.

1850 BC – Amorite warlord Gungunum captures Larsa.

1822 BC – Rimsin becomes king of Larsa. Rivalry and war between Isin and Larsa.

1811 BC – Shamshi-Adad I captures Ekallatum on Tigris.

1810 BC – Rimsin defeats Uruk, Isin and Babylon.

1808 BC – Shamshi-Adad captures Ashur, becomes overlord of Subartu and his elder son, Ishmedagan, rules Ekallatum.

1794 BC – Rimsin vanquishes Isin and begins dating years from his victory.

1796 BC – Shamshi-Adad captures Mari, ousting Zimrilim’s father and puts younger son, Yashmakaddu on the throne.

1792 BC – Hammurabi becomes king of Babylon. At first he is subordinate to Shamshi-Adad.

1780’s BC – Shamshi-Adad campaigns against Yamkhad (Aleppo), Eshnunna and Zagros tribes.

1776 BC – Shamshi-Adad dies. Mari rebels depose Yashmakaddu and Zimri-Lim regains throne of Mari.

1771 BC – Eshnunna supports tribal revolt in kingdom of Mari.

1767 BC – Sheplarpak, high king of Elam allies with Mari against Eshnunna

1766 BC – Eshnunna defeated. Sheplarpak tries to become overlord of Mesopotamia. Hammurabi resolves to resist.

1765 BC – Hammurabi and Mari war against Sheplarpak of Elam and his ally the warlord Atamrum. Siege of Razama.

1764 BC – Siege of Hiritum. Elam defeated and her allies change sides. Rebellion in Eshnunna puts soldier Sillisin on throne.

1763 BC – Hammurabi, annoyed that Rimsin of Larsa remained neutral in the Elamite war, attacks Larsa in alliance with Mari.

1762 BC – Siege and fall of Larsa. Hammurabi annexes Larsa and defeats Eshnunna, Subartu and Gutium; uniting Babylonia.

1761 BC – Zimriliim resists Hammurabi’s demands for city of Hit on Euphrates resulting in war.

1760 BC – Hammurabi makes allies in Subartu, outmanoeuvres Zimrilim, marches on Mari. Zimrilim defeated and Mari falls.

1759 BC – Mari rebels. Final defeat and sack of Mari by Hammurabi.

1740 BC – Assyrian merchant colony at Kanesh (Nesha) in Anatolia, sacked by Hattic king Anitta. Rise of Hittite kingdom.

1728 BC – Samsu-Iluna, Hammurabi’s successor, sacks Shubat-Enlil; former capital of Shamsi-Adad I.

1595 BC – Hammurabi’s dynasty rule Babylonia until Hittite Hattusili I conquers Yamkhad and marches on to sack Babylon.

.

Hammurabi followed the custom of naming his regnal years after events. Here are some significant years:

Year 29 (1764 BC) – Victory over Elam and Guti.

Year 32 (1761 BC) – Larsa comes under Hammurabi’s rule.

Year 33 (1760 BC) – Mari vanquished.

Year 35 (1758 BC) – Mari’s walls demolished in response to rebellion.

Year 37 (1756 BC) – Northern campaign.

Year 39 (1754 BC) – Northern campaign.

Year 38 (1755 BC) – Eshnunna finally defeated.

.

HISTORY: THE AMORITE KINGDOMS

These roving warrior bands became such a nuisance that one of the last Kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur built a huge wall between the Tigris and Euphrates, 170 miles long, to try and keep them out! Contemporary records speak derisively of an uncultured people, ignorant of agriculture, without permanent settlements of any kind. However uncultured they might have been, they were obviously fierce fighters – and numerous!

With the collapse of the Akkadian/Sumerian cities around 2000BC the Amorites poured unchecked into Mesopotamia. They settled amongst the native population, rising to power over them in many cases, taking over existing settlements and establishing their own Amorite dynasties. From this period of anarchy emerged new Amorite Kingdoms. The succeeding four hundred years are sometimes known as the Amorite period of Mesopotamian history (c.2000-1596BC). The new rulers organised their realms quite differently to the earlier centralised states of the Akkadians and Sumerians. Lands that had previously belonged to the temples or the crown were distributed to a new class of landed gentry.

The old temple-based systems of obligatory labour and tithes were replaced with a free citizenry. Where the King and High Priests (often the same person) had previously controlled trade and the distribution of goods, now these things fell into the hands of independent merchants and artisans. This economic and social revolution changed the course of Near Eastern civilisation – heralding the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age (roughly 2000BC-1500BC). In many other respects the culture established by the Akaddians went on much as it had before, the Akkadian language continued to be used – albeit with an admixture of Amorite (itself a western Semitic language) and records continued to be written in the cuneiform script. New gods – such as Marduk – arrived with the Amorites, but old Akkadian and Sumerian gods continued to be worshipped in their age-old temples.

Babylonia under Hammurabi

When it came to warfare the greatest change from previous centuries can be seen in the evolution of the chariot. Technological developments gave warriors stronger, lighter and more efficient wheels. Chariots began to look like what we think of as chariots rather than the earlier four wheeled battle-cars and carts of the Sumerians. The horse began to appear in the Near East during the later part of the Amorite period, replacing the Onager used by the Sumerians.